On September 4, 1957, nine black teenagers tried to make history by desegregating the first school in Arkansas. They would not succeed that day, but by the end of the month, they would. That success was due as much to the steadfast determination and bravery of the students and their families as it was to the support and endless work of Daisy Bates. Though they had no children of their own, Daisy and her husband, L.C., were steadfast advocates of the civil rights movement.

Shortly after they moved to Little Rock, both Daisy and L.C. joined the Arkansas chapter of the NAACP. By 1952, at the age of 34, Daisy was named president of the chapter. Both of the Bateses were well known by this time as they owned and operated an African-American newspaper called the Arkansas State Press. Modeled after existing African-American newspapers in the country, their paper presented news that was not only relevant to, but from a black perspective. There were articles featuring success stories as well as wedding and birth announcements.

However, unlike white papers, the Arkansas State Press also publicized lynchings, cross-burnings and other crimes and injustices that were perpetrated against African Americans yet were largely ignored by the police. As the Civil Rights Movement gained momentum, these stories appeared more and more on the front page of their paper.

For Daisy Bates, this injustice was very personal. Born on November 11, 1914, in Huttig, Arkansas, Daisy was raised by Orle and Susie Smith. It wasn’t until Daisy was a young girl that she found out that the Smiths were not her real parents. When she was three years old, Daisy’s mother was abducted, raped and murdered by three white men. Despite the fact that Huttig was a small company town and it was easy to deduce who the perpetrators were, no charges were ever filed. On the contrary, Daisy’s father received threats and became so fearful for his own life that he fled, leaving Daisy in the care of the family’s friends, the Smiths.

For years, hatred from this injustice filled and threatened to consume her. Not just the injustice shown to her mother, but the fact that all black people felt so helpless to do anything about the treatment they received. They were all stuck in a system rigged to keep them down. Recognizing that this hatred would eventually be her downfall, Orle urged Daisy, from his death bed, to use her hatred for good and to turn it into action that would make things better. The NAACP provided Daisy with a platform for that action.

In 1954, a major blow was dealt to the Jim Crow laws of the south. In the monumental case of Brown vs Board of Education, the Supreme Court ruled that separate was not equal and that schools were no longer allowed to segregate their pupils based on the color of their skin. Following this ruling, schools across the country were desegregated. However, the state of Arkansas drug its feet. The school districts, backed by the governor, hemmed and hawed and found one reason after another to postpone desegregation.

Superintendent Blossom, from Little Rock, and Governor Faubus eventually developed a gradual three-year integration proposal, but they failed to implement it. By 1956, the NAACP declared that enough was enough and filed a lawsuit against the Little Rock School District. As the president of Arkansas chapter, Daisy Bates became the face of desegregation in Arkansas. She was called upon to testify, and it was here that she publicly started laying the groundwork for equality.

There were many ways, many of them subtle and insidious, that white people expressed their imagined superiority over black people. One of those ways was to always refer to black people by their first name, regardless of age. Therefore, during the trial, the attorneys and the judge referred to all of the white people present as Mr. or Mrs. but referred to Daisy Bates as simply Daisy. Refusing to play by their rules and accept that she wasn’t due the respect that the white people in the court were due, she refused to respond until the school board’s attorney referred to her as Mrs. Bates.

With this small but important victory, Mrs. Bates had drawn the first line in the sand, and she had no plans of ever crossing back over. The next line was drawn when the ruling came back ordering that the Little Rock School Board must begin their integration process in September of 1957. While this was a major win for the NAACP and the Civil Rights Movement, the real work hadn’t even begun.

Mrs. Bates threw herself into preparations trying to find students and families that were willing to try to attend the all-white Central High School in Little Rock. Per the school board’s gradual integration plan, black students would be introduced at the high school level first. If that worked, then the following year black students would be introduced at the junior high level and then the year following that at the grade school level.

Mrs. Bates meticulously chose which students to approach. She wanted bright, responsible and promising students who had the potential to go far in life. Essentially, students that on paper any school would love to have. This type of student was also the obvious choice because this type of student would be willing to literally walk the gauntlet every day in order to receive a better education.

In the end, Mrs. Bates recruited nine students, six young women – Gloria Ray, Melba Patillo, Elizabeth Eckford, Minnijean Brown, Carlotta Wells and Thelma Mothershed – and three young men – Terrence Roberts, Ernest Green and Jefferson Thomas. They would become known as the Arkansas Nine.

In the months leading up to September, Mrs. Bates worked with the nine students, getting them enrolled at the school, coaching them on how to respond to reporters’ questions and teaching them coping skills for the abuse that they would encounter while in the school. She impressed upon them that no matter what happened, they could not become violent. Mrs. Bates procured donations of new clothes and appointments at salons and barbershops to ensure that the nine would look as well put-together as their white counterparts. She not only worked with the students but also kept in constant contact with the parents attempting to allay their fears.

However, their fears were justified.

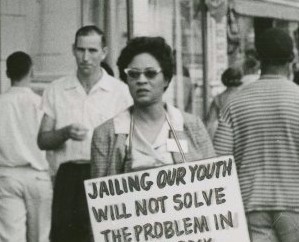

As the impending integration date approached, the white community lashed out more and more. The Bateses, the students and their families were subjected to insults yelled at them whenever they were in public and harassment at their homes, which included everything from rocks being thrown through windows to crosses being burned on their front lawn. Before the school year was over, one girl’s father had even lost his job.

It was because of this, that on the eve of integration Mrs. Bates, fearing for the very lives of her students – after all the Governor had practically promised that blood would run in the streets if the integration proceeded – called every priest and minister in Little Rock until she had four ministers who had agreed to walk with the students into the school in the hopes of not only affording what protection a man of the cloth could give, but also as a statement that God was on their side.

All of the students were notified by telephone of this last minute change of plan, except for one. Elizabeth Eckford’s family did not have a phone and after staying up all night making arrangements and then fielding the onslaught of reporters in the morning, Mrs. Bates forgot to drive out to the Eckford’s to inform them of the new plan. So it was with four ministers, her husband and the other eight students that Mrs. Bates first heard the reports of a lone black student attempting to make her way to the front of the school.

Realizing the horrible oversight, Mr. Bates raced in their car to the other side of the school to try to save Elizabeth from the mob. Hundreds of people were gathered in front of the school hurling insults and threatening violence to both journalists and activists alike. Upon seeing Elizabeth, they surrounded her. The governor had called out the Arkansas National Guard who had taken up positions surrounding the school, but it became clear very quickly that they hadn’t been ordered there to protect the black students. They had been ordered there to prevent the black students from entering. Elizabeth was able to escape the crowd relatively unscathed, but she hadn’t been able to get anywhere near the school.

Realizing that trying to send the remaining students in was suicide, the Arkansas Nine retreated.

Once more, Mrs. Bates found herself going head to head with the school board and the Governor. Not knowing how long this stalemate would last, she arranged for a space and for tutors for the nine students so that when they finally did get through the doors of the school, they wouldn’t be behind. That taken care of, Mrs. Bates appealed to President Eisenhower to intervene. If a Supreme Court ruling wasn’t enough to get the black students in, then maybe a presidential edict would do the trick.

When it was apparent that nothing else was going to work, President Eisenhower made history as the first president to ever have to use Federal powers to enforce a Federal ruling. Not only did he send in the 101st Airborne Division, but he federalized the Arkansas National Guard and sent them in for back up.

On September 25th, the Arkansas Nine assembled at the Bates’s house, and under the protection of the 101st Airborne Division, they made their way to the high school. Even with an armed guard, it was obvious that there would be bloodshed if the students attempted to enter through the front door, so they were silently slipped through a side door. When the mob outside the school discovered this, they were outraged, and it was only the armed troops that kept the school from being mobbed.

Reports of verbal and physical abuse of the nine black students flooded the media, but Mrs. Bates remained in constant contact with the school and was able to reassure the parents of the students that these were rumors. However, with the threats escalating, the students were removed from school before the end of the day for their safety.

The next day was much the same. The students assembled at the Bates’s house and were escorted into the school by armed guards. This time, to ensure their safety, each student was assigned an Airborne guard who would walk with the student in between each class and then stand ready outside the classroom during class. After school, they were all escorted back to the Bates’s house.

This routine continued until the mobs quieted down and the Federal troops were withdrawn, leaving the National Guard to stand watch. However, without the Federal presence the situation deteriorated. The taunts and abuse flung at the students made school a living hell and constant threats made their lives outside of school precarious. The Bates’s house became such a target that a cadre of volunteers was formed in order to provide a 24-hour watch to keep them safe. Even with these precautions, the local police officers found excuses to arrest the volunteer watchmen, leaving the house open for attack, including a brick thrown through the front window with a note attached promising that the next thing flung through the window would be dynamite.

Mrs. Bates herself was even verbally attacked in the media, with some people claiming that the only reason she was doing what she was doing was because she wanted to be famous. Eventually, it became obvious that the National Guard was failing to adequately protect the nine students, so Federal troops were ordered back in as escorts. All nine students were able to finish out the school year, one even graduating, and miraculously sustaining minimal bodily injury.

The National Council of Negro Women named Daisy Bates the 1957 Woman of the Year and the NAACP awarded their Springarn Achievement Medal to Bates and the Arkansas Nine in 1958. Central High School in Little Rock had been successfully desegregated. Unfortunately, the school board was not willing to accept defeat that easily.

Knowing full well that the powers that be in Washington DC would force the school board to follow their desegregation plan and integrate the junior highs starting in 1958, they simply closed down the schools instead. Now known as “The Lost Year,” the 1958-1959 school year throughout all of Arkansas was cancelled.

They also went after the NAACP, demanding that they turn over their enrollment records, and then arresting Mrs. Bates and the other Little Rock officials when they refused. Once more, the NAACP went to court and fought all the way to the Supreme Court level before the case was overturned, which kept the enrollment records private and undoubtedly saved lives.

Unable to cancel yet another school year, the schools reopened in the fall of 1959 and desegregation marched forward. Mrs. Bates continued to receive threats, and in October, the Arkansas State Press folded. The majority of the paper’s big advertisers had pulled out years earlier in protest of Mrs. Bates’s desegregation activities, but they had managed to scrape by and keep the paper running with contributions that came through the mail. Sadly, it wasn’t enough to keep the paper going, and the last issue went to press on October 29, 1959.

Needing a break from the constant danger and harassment, Mrs. Bates moved to New York City in 1960 and wrote her memoir The Long Shadow of Little Rock. It was published in 1962 with a foreword by Eleanor Roosevelt. Mrs. Bates then moved to Washington DC to work for the Democratic National Convention and on anti-poverty projects for President Johnson.

In 1963, she was asked to speak at the March on Washington. She was the only woman to formally address crowd, and she did so after Martin Luther King Jr. delivered his iconic “I Have a Dream” speech. Mrs. Bates continued her work in DC until she returned to Little Rock in 1965 to recover from a minor stroke.

In 1968, sufficiently recovered, Mrs. Bates moved to Mitchellville, Arkansas, to put into action some of the work that she had done in her anti-poverty projects in DC. Mitchellville was an exclusively black community, living well below the poverty level.

Mrs. Bates established the Mitchellville Office of Economic Opportunity Self-Help Project in the hopes of proving that poor blacks could help themselves if they were only shown how and given the proper resources. With the work of the community, the project built a new sewer and water system, paved the streets and erected a community center, which housed resources for the people of the community. Mrs. Bates would drive back to Little Rock on the weekends to be with her husband, and continued this work, watching the community grow and improve, until she retired in 1974.

She received the Arkansas General Assembly Commendation in 1975 and an honorary Doctor of Laws degree from the University of Arkansas in 1984. That year she also resurrected the Arkansas State Press, but without her husband to run it with her (he had died in 1980), she sold the paper in 1987, staying on as a consultant. The Arkansas Press published a reprint of her memoir in 1986, which went on to win the American Book Award in 1988.

Mrs. Bates lived out the rest of her years quietly, succumbing to a heart attack one week before her 85th birthday on November 4, 1999. She became the first, and to this date the only, black person to lie in state in the Arkansas Capital.

To honor the work that she did, officials renamed the street that runs to the north of Central High School in Little Rock after her, and there is also a Daisy Bates Elementary School. The state of Arkansas also made a declaration that the third Monday in February is not only George Washington’s birthday but also Daisy Gatson Bates day, an official state holiday. There was a celebration held at the Clinton School of Public Service in Mrs. Bates’s honor on what would have been her 100th birthday, November 11, 2014. Ernest Green, one of the Little Rock Nine, gave a speech in commemoration of her many achievements.