On April 19, 1955, in Montgomery, Alabama, a black woman kicked up a stir and was arrested for refusing to relinquish her seat to a white customer on a city bus. This simple act was a protest of more than the unfair city statutes. In addition to the racist bus statutes, white bus drivers often mistreated their black passengers. They were known to be verbally abusive, to skip all-black stops, and would do things such as collect a fare but drive off before the black person had time to board the bus. This behavior was not only expected but also resignedly accepted as the status quo in Alabama. A black woman refusing to play by the white man’s rules was a new occurrence, especially since the threat of arrest didn’t persuade her to move. She remained resolutely seated until the police came and took her away.

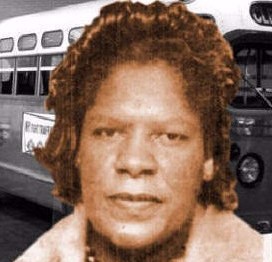

This story should sound very familiar. However, the name that you have associated with this deed is Rosa Parks, but Parks wasn’t arrested until December of 1955. Her act of civil disobedience was the mirror image of Aurelia Browder’s, which had occurred eight months earlier, with one notable exception: Aurelia was only charged with breaking the city bus statute, while Rosa was charged with disorderly conduct in addition to breaking the statute. It is this difference that thrust Rosa Parks into the spotlight, and kept Aurelia Browder’s name in the shadows despite the fact that she was the lead plaintiff in the lawsuit that was responsible for ending the segregation of buses in Alabama.

Born on January 29, 1919, in Montgomery, Alabama, Aurelia had grown up entrenched in Jim Crow laws. Despite this, she was able to eke out a living for herself. She graduated with honors from Alabama State University with a BS degree and worked in a number of different jobs, including seamstress, nurse, midwife, and teacher. As a widow, she was the sole provider for her six children. As the Civil Rights Movement began, Aurelia became involved, hoping to provide a better life for herself and her children. During the voter campaigns of the early 1950s, Aurelia helped fight to get the poll tax removed and volunteered her time to tutor black registrants so they could pass the voter test. She even went so far as to drive people who had no transportation to the polls or the registration office. If there was anything she could do to help a black person vote, she was there. Aurelia was also a member of the NAACP, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), the Women’s Political Council (WPC), and the Montgomery Improvement Association (MIA).

On March 2, 1955, Claudette Colvin lit a spark by refusing to give up her seat on a city bus and was arrested. Aurelia followed suit and was arrested on April 19, followed by the arrests of Mary Louise Smith, Susie McDonald, and Jeanatta Reese. The straw that broke the camel’s back was the arrest of Rosa Parks on December 1. MIA used this final arrest as the incendiary incident to launch the famous Montgomery Bus Boycott on December 3, 1955. MIA had three main demands that had to be fulfilled in order for them to cease the boycott. First, all passengers were to be treated courteously by the drivers. Second, seating was to be based on a first-come, first-served basis. Third, blacks were to be employed to drive the predominantly black routes.

As a member of MIA, Aurelia was highly involved in the boycott. She volunteered her time and her car to offer rides to those avoiding the bus. MIA, with the help of local churches, held drives for new shoes to replace those being worn out from all of the walking. Black taxi drivers helped out by offering rides to blacks for 10 cents, which was the same price as a bus fare. Through all of these initiatives, the boycott’s success was instantaneous and far-reaching. The city buses were empty and the streets were filled with black people walking. The city tried pressuring insurance agencies to stop insuring the boycotter’s cars.

However, MIA, with the help of the NAACP, simply arranged policies through Lloyd’s of London.

The second prong of attack was a civil action lawsuit filed by lawyers Fred Gray and Charles D. Langford with help from the NAACP and Thurgood Marshall. Rosa Parks, the poster child of the bus boycott, would have been the obvious choice to be the lead plaintiff. She was seen as a pillar of the community and everybody already knew her name. However, since her arrest record included the charge of disorderly conduct, the lawyers were afraid that that would only hurt their case by tying it up in local jurisdictions where they were guaranteed to lose. The next obvious choice would have been Claudette Colvin, as she was the first arrest and had started the ball rolling, creating a bit of a sensation since she was only 15 at the time. Unfortunately, Colvin had a reputation for being outspoken and fond of swearing, not to mention that she had just given birth to a son in December.

Gray and Langford knew that they needed the perfect citizen: hard working, clean-cut, responsible, and well spoken. Aurelia Browder fit this description, so they placed the burden of this lawsuit on her shoulders. Colvin, Smith, McDonald, and Reese were also plaintiffs, but Reese withdrew her name due to intimidation from the white community. With their plaintiffs in order, Gray and Langford filed Browder v. Gayle – William A. Gayle was the Mayor of Montgomery – on February 1, 1956. The lawsuit challenged the legality of the Alabama state statutes and the Montgomery city ordinances requiring segregation on buses. The suit further challenged that segregation on privately owned buses that were operated by the city was a violation of the 14th Amendment.

On May 11, Browder and the other plaintiffs testified before a three federal judge panel, whose final ruling on June 5, with a 2:1 vote, was that segregated buses were unconstitutional. It was decided that the same precedent used in Brown v. Board of Education could be applied to Browder v. Gayle. Separate was not equal. This was huge win for MIA and the NAACP. However, as the city of Montgomery was appealing the decision to the Supreme Court, it was announced that the bus boycott would be continued until the ruling was implemented. The proceedings dragged on through the summer and into the fall leaving the plaintiffs, especially Aurelia as the lead, open to intimidation and threats. Finally on November 13, 1956, the Supreme Court upheld the decision of the three judge panel and on December 17 rejected the city and state appeals to reconsider.

Segregation of buses had been deemed unlawful, fully legitimizing the bus boycott.

On December 20, 1956, 380 days after the boycott started, the order that all buses must be integrated arrived in Montgomery. MIA voted to end the boycott and Martin Luther King Jr. encouraged all black people in Montgomery to begin riding the non-segregated buses the next day. This marked one of the first major victories in the Civil Rights Movement. Despite the fact that her name is down in the books for this landmark legal case, Aurelia Browder’s involvement remains hidden in the shadows. After the case was settled, she remained active with the NAACP, MIA, WPC, and SCLC. For a time, she taught veterans at the Loveless School, and also established her own business. She passed away on February 4, 1971. Aurelia Browder and the other three plaintiffs were finally recognized for their efforts in 2004, with a roadside monument.